Rosalind Williams, Dream Worlds

The Electrical Fairyland

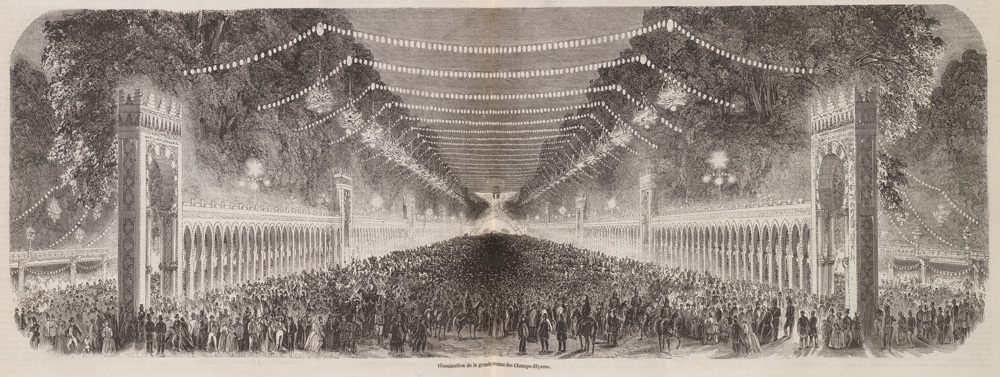

Illumination of the Champs Elysees 1853

The Electrical Fairyland -- By now it is becoming clear how momentous were the effects of nineteenth-century technological progress in altering the social universe of consumption. Besides being responsible for an increase in productivity which made possible a rise in real income; besides creating many new products and lowering the prices of traditional ones; besides all this, technology made possible the material realization of fantasies which had hitherto existed only in the realm of imagination. More than any other technological innovation of the late nineteenth century, even more than the development of cinematography, the advent of electrical power invested everyday life with fabulous qualities. The importance of an electrical power grid in transforming and diversifying production is obvious, as is its eventual effect in putting a whole new range of goods on the market. What is less appreciated, but what amounts to a cultural revolution, is the way electricity created a fairyland environment, the sense of being, not in a distant place, but in a make-believe place where obedient genies leap to their master's command, where miracles of speed and motion are wrought by the slightest gesture, where a landscape of glowing pleasure domes and twinkling lights stretches into infinity.

Above all, the advent of large-scale city lighting by electrical power nurtured a collective sense of life in a dream world. In the 1890s nocturnal lighting in urban areas was by no means novel, since gas had been used for this purpose for decades; however, gas illumination was pale and flickering compared to the powerful incandescent and arc lights which began to brighten the night sky in that decade. The expositions provided a preview of the transformation of nighttime Paris from somber semidarkness to a celestial landscape. At the 1878 exposition an electric light at a cafe near but not actually on the fairgrounds caused a sensation. In 1889 a nightly show of illuminated fountains entranced crowds with a spectacle of falling rainbows, cascading jewels, and flaming liquids, while spotlights placed on the top of the Eiffel Tower swept the darkening sky as the lights of the city were being turned on. At the 1900 exposition electrical lighting was used for the first time on a massive scale, to keep the fair open well into the night. Furthermore, the special lighting effects were stunning. In one of his articles for the Revue de Paris, Corday describes the nightly performance:

A simple touch of the finger on a lever, and a wire as thick as a pencil throws upon the Monumental Gateway ... the brilliance of three thousand incandescent lights which, under uncut gems of colored glass, become the sparkling soul of enormous jewels.

Another touch of the finger: the banks of the Seine and the bridges are lighted with fires whose reflection prolongs the splendor. . . The façade of the Palace of Electricity is embraced, a stained-glass window of light, where all these diverse splendors are assembled in apotheosis.

Like the technological marvels already mentioned, this one was at once exploited for commercial purposes. As early as 1873 the writer Villiers de l'Isle-Adam (1838-1889) predicted in a short story, "L'Affichage célèste" (which might be loosely translated as "The Heavenly Billboard "), that the "seeming miracles" of electrical lights could be used to generate "an absolute Publicity" when advertising messages were projected upward to shine among the stars:

Wouldn't it be something to surprise the Great Bear himself if, suddenly, between his sublime paws, this disturbing message were to appear: Are corsets necessary, yes or no? ... What emotion concerning dessert liqueurs ... if one were to perceive, in the south of Regulus, this heart of the Lion, on the very tip of the ear of corn of the Virgin, an Angel holding a flask in hand, while from his mouth comes a small paper on which could be read these words: My, it's good!

Thanks to this wonderful invention, concluded Villiers, the "sterile spaces" of heaven could be converted "into truly and fruitfully instructive spectacles. . . . It is not a question here of feelings. Business is business. . . . Heaven will finally make something of itself and acquire an intrinsic value. '' As with so many other writers of that era, Villiers's admiration of technological wonders is tempered by the ironic consideration of the banal commercial ends to which the marvelous means were directed. Unlike the wonders of nature, the wonders of technology could not give rise to unambiguous enthusiasm or unmixed awe, for they were obviously manipulated to arouse consumers' enthusiasm and awe.

The prophetic value of Villiers's story lies less in his descriptions of the physical appearance of the nocturnal sky with its stars obscured by neon lights, than in his forebodings of the moral consequences when commerce seizes all visions, even heavenly ones, to hawk its wares. Villiers's prophecies were borne out by the rapid application of electrical lighting to advertising. As he foresaw, electricity was used to spell out trade names, slogans, and movie titles. Even without being shaped into words, the unrelenting glare of the lights elevated ordinary merchandise to the level of the marvelous. Department-store windows were illuminated with spotlights bounced off mirrors. At the 1900 exposition, wax figurines modeling the latest fashions were displayed in glass cages under brilliant lights, a sight which attracted hordes of female spectators. When electrical lighting was used to publicize another technical novelty, the automobile, the conjunction attracted mammoth crowds of both sexes. Beginning in 1898, an annual Salon de l' Automobile was held in Paris to introduce the latest models to the public. It was one of the first trade shows; the French were pioneers in advertising the automobile as well as in developing the product itself. This innovation in merchandising- like the universal expositions the Salon de I'Automobile resembles so closely claimed the educational function of acquainting the public with recent technological advances, a goal, however, which was strictly subordinate to that of attracting present and future customers. The opening of the 1904 Salon de l'Automobile was attended by 40,000 people (compared to 10,000 who went to the opening of the annual painting salon), and 30,000 came each day for the first week. Each afternoon during the Salon de I' Automobile, the ChampsÉlysées was thronged with crowds making their way to the show, which was held in the Grand Palais, an imposing building constructed for the 1900 universal exposition. During the Salon the glass and steel domes of the Grand Palais were illuminated at dusk with 200,000 lights; the top of the building glowed in the gathering darkness like a stupendous lantern. People were enchanted: "a radiant jewel, "they raved,"a colossal industrial fairyland," "a fairy tale spectacle." Inside, lights transformed the automobiles themselves into glittering objects of fantasy:

You must come at nightfall. Coming out into the world from the entrance to the Metro, you stand stupefied by so much noise, movement, and light. A rotating spotlight, with its quadruple blue ray, sweeps the sky and dazzles you; two hundred automobiles in battle formation look at you with their large fiery eyes . inside, the spectacle is of a rare and undeniable beauty. The large nave has become a prodigious temple of Fire; each of its iron arches is outlined with orange flames; its cupola is carpeted with white flames, with those fixed and as it were solid flames of incandescent lamps: fire is made matter, and they have built from it. The air is charged with a golden haze, which the moving rays of the projectors cross with their iridescent pencils. . . .

Again this is an aesthetic of the exaggerated and showy, of simple but powerful imagery repeated to overwhelm the viewer (what could be more repetitious than two hundred thousand lights?). As with exotic decor, the purpose behind such a display is to win attention and to raise merchandise above the level of the everyday by associating it with exciting imagery. Unlike images of far-off places, however, a fairyland cannot be accused of falsity because it never pretends to be a real place. Or can it? Electric lighting covers up unpleasant sights which might be revealed in the cold light of day. The illumination of the Grand Palais disguised the building itself. In the words of one visitor:

The Grand Palais itself is almost beautiful because you hardly see it anymore: the confused scrap-iron and copperwork ... [is] lost in the shadow; the luminous scallop decorations and chandeliers and ... allegories, drowned in the irradiation .. ... The roof itself, that monstrous skin of a leviathan washed up there on the bank of the river, borrows a sort of beauty from the light which emanates from it.

. . . . Through fantasy, business provides alternatives to itself. If the world of work is unimaginative and dull, then exoticism allows an escape to a dream world. If exotic decor is heavy, unconvincing, and shabby, then another level of deception is furnished by a nightly fairyland spectacle that waves away the exotic with the magic wand of electricity. Robert de La Size ran ne, art critic for the Revue des deux modes, compared the Salons de l'Automobile to fairy tale princesses fought over by "perverse and benevolent powers" so that they were "frightfully ugly all day long [and] at night [became] beauties adorned with dazzling jewels." According to La Sizeranne, this diurnal schizophrenia was being repeated all over Paris. In the day the city displayed "superfluous, ignoble, lamentable ornaments," while at nightfall "these trifling or irritating profiles are melted in a conflagration of apotheosis.... Everything takes on another appearance," the ugly details are lost, and diamonds, rubies, and sapphires spill over the city. Instead of correcting its mistakes, the city buries them under another level of technology. In this respect the whole city is assuming the character of an environment of mass consumption. In the day as well as at night, the illusions of these environments divert attention to merchandise of all kinds and away from other things, like colonialism, class structure, and visual disasters.

How much of the history of consumption is revealed in comparing Mme. de Rambouillet's salon of witty conversation and candlelight with the twentieth-century Salon de l'Automobile, a cacophony of crowds, cars, glass, steel, noise, and light!

The Champ De Mars and the Pavillon De L"Electricité De Nuit, 1900 Paris Exhibition

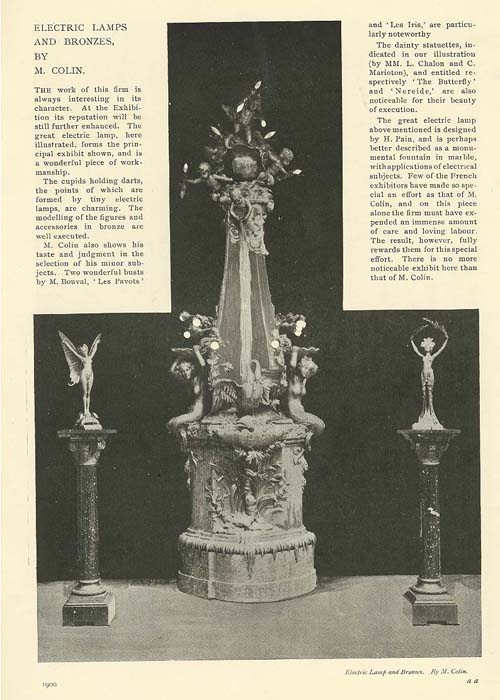

Electric Lamps Displayed at the 1900 Paris Exhibition